On Wednesday, the Design Review Committee gave final approval to the new Westin Hotel and “Marketplace” entertainment district adjacent to the Convention Center downtown. While earlier renderings of the hotel had been made public, this was the first public unveiling of the Marketplace. Does it meet expectations?

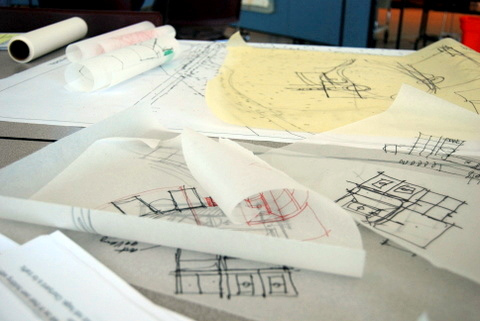

Above are the two principal architects of this project, Joe Rabun of Rabun Rasche Rector Reese from Atlanta (Hotel) and Fred Keith of Keith Design from Birmingham (Marketplace) presenting to the DRC. The buildings are designed in a modest “contemporary” style familiar from corporate-type projects across the US; a palette of red and iron-spot brick, gray metal panels, and dark bronze storefront members are put together as one may expect. The architecture itself is not the question of the day, but the urbanity of the plan, and whether it helps the BJCC overcome its current isolation and lack of connectivity.

Above is the plan layout of the site: the Westin and Marketplace are towards the top; the existing parking deck to the lower left; and a proposed surface lot to the lower right. Keep in mind that over the last decade or so, the BJCC has acquired an enormous amount of property, so at this point there is no surrounding context except the BJCC itself–all else has been demolished. Note that 23rd Street, moving North-South through the middle, has been blocked off by the Marketplace; a new East-West street (called Main Street we hope temporarily) has been created to bisect the Marketplace. This new street curves around at one end past the Westin, and at the other past a site for a future second hotel.

This new street will be “private”, owned by the BJCC. Private streets are typically the domain of gated subdivisions or shopping malls, not downtowns. And this is the first element that gives one pause: a part of the public domain (23rd Street) has been eliminated, and a private street laid out instead. The way this street is totally self-contained, as opposed to the typical open-ended gridded street downtown, is again a reminder of suburban planning with its cul-de-sacs and limited-access roads.

The view above is on this new private street, looking west towards the hotel. There are some basic urban elements that are good–the storefronts (with clear, not tinted, glass for maximum visibility and synergy between indoor and outdoor activity) fronting on sidewalks, cafe tables on these sidewalks, canopies, thoughtful street furnishings. But the overall impression is less that of a vibrant city block, and more a vibrant suburban strip mall. Why? Because downtown blocks are messy, varied, and full of surprises. This is part of what makes the public realm fascinating and vital (but also frustrating on certain levels). Suburban strip malls are clean, homogeneous, and predictable. This is part of what makes the privatized-quasi-public realm fascinating and vital (but again frustrating on different levels). Anytime you take a single owner (mall developer or BJCC) and ask a single architect to design a place, it’s a very, very hard trick to pull off a simulation of the urban variation you get in a true city. Paris is wonderful in part because yes, there was a very, very heavy master hand guiding its development in the 19th century–but many different architects designed the buildings which conformed to the plan with individual flair and detailing. Birmingham is a starker example, where downtown (and to a lesser extent downtown Homewood, or even Mountain Brook Village) contains numerous styles and periods, some good, some not so, but overall giving a pleasantly varied aspect. In this instance, the BJCC could have come up with a master plan and then allowed multiple architects to create individual buildings–but that choice would be an unusual one.

Which brings us to the Richard Arrington Blvd. elevation shown above (and seen at the top of the plan). The very small blocks created by the new “Main Street” allow only 60-70 feet of depth for the buildings. Yet the buildings are rendered with full public storefronts and cafe seating not just facing Main Street, but facing Richard Arrington to the north and the surface parking to the south. When questioned about how a restaurant could have two public storefronts with such a small depth, the answer was that, well, in reality there would probably not be two “fronts”–the (as-yet unsigned) tenants would typically want to face Main Street, and the storefront on the other end would be “modified” in some way. As in eliminated. Maybe not altogether–yes maybe it’s possible–but I share the concern of the Committee that this is another element which will make the project turn inward, focused only on the private street, rather than also reaching outwards.

And take the clump of cafe tables and umbrellas you see on the corner in the rendering above: not only is it doubtful people will be clustering on both sides like this, but the sides of the buildings are actually large trash enclosures. Another suburban-style element you’d rather not see facing a public street downtown. Or even a private street.

The shot above of the original courtyard in the BJCC, designed in the late 1960’s, has a caption that’s a bit unfair. On the one hand, the Marketplace and Westin do have restaurants facing the street and pedestrian scale; there are some solid “urban” elements in place in stark contrast to the “bunker” design of the original. But on the other hand the project’s insularity is reminiscent of that original design, at least in principle. Urbanistically it’s better, but is it better enough? I hope that this project is profitable for the BJCC and the City, that visitors have something to eat and entertain themselves with, and that perhaps over time the district will become more varied and feel more organic. I think it could succeed on a certain level: that of being competitive with other convention centers that have more hotel rooms and amenities at their doorsteps. For this reason alone, the project really had to happen in some way.

But the wish that this could become a new, vibrant neighborhood with linkages to Norwood and the CBD, seems remote. A long-term plan that illustrates how this first, uncertain piece could grow and extend and connect would be worthwhile. Decent contemporary detailing is good; LEED certification is good; amenities next to our convention center are good. A visionary place that rises above the merely practical would be even better.

A final note–at the end of the presentation, committee member Cheryl Morgan argued that the skywalk connecting the Westin to the parking deck (and thus to the Sheraton and BJCC) was anti-urban, anti-pedestrian, and unwise for the health of the Marketplace. If people at the hotel are to patronize shops and restaurants on the street, they should be walking down a sidewalk to get to their hotel, not going straight from their car into the building (tangential thought: many occupants of 4-star hotels probably valet anyway). The BJCC representative replied that while they wanted lots of pedestrian activity, to be competitive they had to allow people to walk from one end of the complex to the other completely out of the weather. Above is the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, built in 1997, which at the time made the controversial decision to build the parking deck across the street, to force patrons (in downtown Newark no less) to walk on sidewalks. Rain or shine. Lo and behold, vacant storefronts across the street started filling with restaurants due to all the people walking on the streets. It’s too bad more of this mentality hasn’t infiltrated the thought process in this City generally. If we really want to be known as “green”, encouraging vibrancy that connects rather than insulates–we need to be thinking more like that. No one architect or “Marketplace” can solve the isolation issues of the BJCC. But a great master plan for the district could.

[thanks to Keith Design for the renderings, and kwatson0013 for the Newark pic]